|

FAMOUS SHIPS |

|

FAMOUS SHIPS |

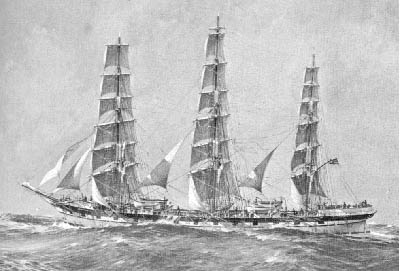

THE "Cromdale "

This ship was launched from Barclay, Curle & Co.’s yard on the Clyde in June, 1891. Her measurements were: tonnage, 1,903; length, 271 feet 6 inches; breadth, 40 feet 1 inch; and depth, 23 feet 4 inches. Her owners, Messrs. Donaldson, Rose & Co. put her into the Sydney trade, her first commander being Captain E. H. Andrews. The main interest in this ship was a result of her very first voyage. On her way back home she became trapped in a vast island of ice.

At varying times the Antarctic region losses great chunks of its ice barrier bordering the continent of the South Pole. Usually this has little effect on the ship traffic going around the Horn, but in 1892-93 a very severe breakage of ice resulted in very large ice flows around the Horn which endangered all shipping going around the Horn. These ice burgs make the one the Titanic ran into look small. They were reported to have been bergs and islands of ice rising to 1,000 and even 1,500 feet sheer out of the sea! There was one ship, the GUIDING STAR, that was back-strapped under the huge ice cliffs and lost with all hands. Captain Andrews account of what happened to the CROMDALE is related as follows:

"We left Sydney on 1st March (1892), and having run our

easting down on the parallel of 49 degrees to 50 degrees south, rounded the Horn on 30th

March, without having seen ice, the average temperature of the water being 43 degrees

during the whole run across.

"We left Sydney on 1st March (1892), and having run our

easting down on the parallel of 49 degrees to 50 degrees south, rounded the Horn on 30th

March, without having seen ice, the average temperature of the water being 43 degrees

during the whole run across.

At midnight on 1st April, in 56 degrees South, 58 degrees 32’ West, the temperature fell to 37 ½ degrees, this being the lowest for the voyage, but no ice was seen, though there was a suspicious glare to the southward.

At 4 a.m. on 6th April, in 46 degrees South, 36 degrees West, a large berg was reported right ahead, just giving us time to clear it. At 4:30, with the first signs of daybreak, several could be distinctly seen to windward, the wind being N.W., and the ship steering N.E. about 9 knots. At daylight, 5:20 a.m., the whole horizon to windward was a complete mass of bergs of enormous size, with an unbroken wall at the back; there were also many to leeward.

I now called all hands, and after reducing speed to 7 knots, sent the hands to their stations and stood on. At 7 a.m. there was a wall extending from a point on the lee bow to about 4 points on the lee quarter, and at 7:30 both walls joined ahead. I sent the chief mate aloft with a pair of glasses to find a passage out, but he reported from the topgallant yard that the ice was unbroken ahead. Finding myself embayed and closely beset with innumerable bergs of all shapes, I decided to tack and try and get out the way I had come into the bay.

The cliffs were now truly grand, rising up 300 feet on either side of us, and as square and true at the edge as if just out of a joiner’s shop, with the sea breaking right over the southern cliff and whirling away in a cloud of spray.

Tacked ship at 7:30, finding the utmost difficulty in keeping clear of the huge pieces strewn so thickly in the water and having on several occasions to scrape her along one to keep clear of the next.

We stood on this way until 11 a.m., when, to my horror, the wind started to veer with every squall till I drew quite close to the southern barrier, having the extreme point a little on my lee bow.

I felt sure we must go ashore without a chance of saving ourselves. Just about 11:30 the wind shifted to S.W., with a strong squall, so we squared away to the N.W., and came past the same bergs as we had seen at daybreak, the largest being about 1,000 feet high, anvil-shaped. At 2 p.m. we got on the N.W. side of the northern arm of the horseshoe-shaped mass. It then reached from 4 points on my lee bow to as far as could be seen astern in one unbroken line.

A fact worthy of notice was that at least 50 of the bergs in the bay were perfectly black, which was to be accounted for by the temperature of the water being 51 degrees, which had turned many over. I also think that had there been even the smallest outlet at the eastern side of this mass, the water between the barriers would not have been so thickly strewn with bergs, as the prevailing westerly gales would have driven them through and separated them.I have frequently seen ice down south, but never anything like even the smaller bergs in this group."

This was the most exciting time for the CROMDALE. Her best passage was made in 1894, 80 days from Sydney. In 1898 Captain Sibley took over command. She was a smart ship and the sailors aboard her were proud of their ship. She was what was termed a "happy" ship with a splendid crew who took pride in smartness about her decks and tophamper.

Her last voyage was under Captain Arthur, of Dundee. It was an unlucky voyage from the beginning. The second mate drowned, the bos’n fell down the hold and was killed and a seaman later followed the bos’n’s example and was also killed. On sailing back from Taltal for the United Kingdom on January 19th, 1913, she ran into very thick fog and struck right at the foot of the cliff under the Lizard. Captain Arthur, his wife, and the crew of 23 hands pulled safely away from the ship’s side, since the CROMDALE was badly holed.

Those on duty at Lloyd’s signal station realized something was wrong and dispatched the life-boats, who rescued the people. But the captain and a few sailors decided to go back aboard the wreck, as the sea was calm. They managed to save all the fo’c’sle kits and the ships papers. The Lizard life-boat brought them off again when the ship suddenly settled and those still aboard had to take to the rigging to stay above water. The sea remained calm, but the Atlantic swell soon broke the ship up – there was no chance to salvage her.